The Shearing of Women

WWII Vengeance in France (and beyond)

I have written a couple of posts this month about women during and after the war, particularly in France (a nation which this month celebrated the 80th anniversary of women getting the vote).

To end the month, I want to tell the other side of the story. Here is a long-read article about one of the most controversial postwar reactions to the Nazi occupation: the punishment of women who slept with German soldiers by shaving their heads.

This is a long-read essay, so at some point towards the end you will hit a paywall. There is plenty to get your teeth into before that point – but if you feel like reading more, and want to support my work, please consider becoming a paying subscriber.

In the autumn of 1944, a young girl from Saint-Clément in the Yonne department of France was arrested for having ‘intimate relations’ with a German officer. When questioned by the police she openly admitted to her affair. ‘I became his mistress,’ she said. ‘He sometimes came to the house to help my father when he was ill. When he left, he gave me his Feldpost number. I wrote to him and had my letters taken to him by other Germans because I could not use the postal services in France. I wrote to him for two or three months but I do not have his address anymore.’

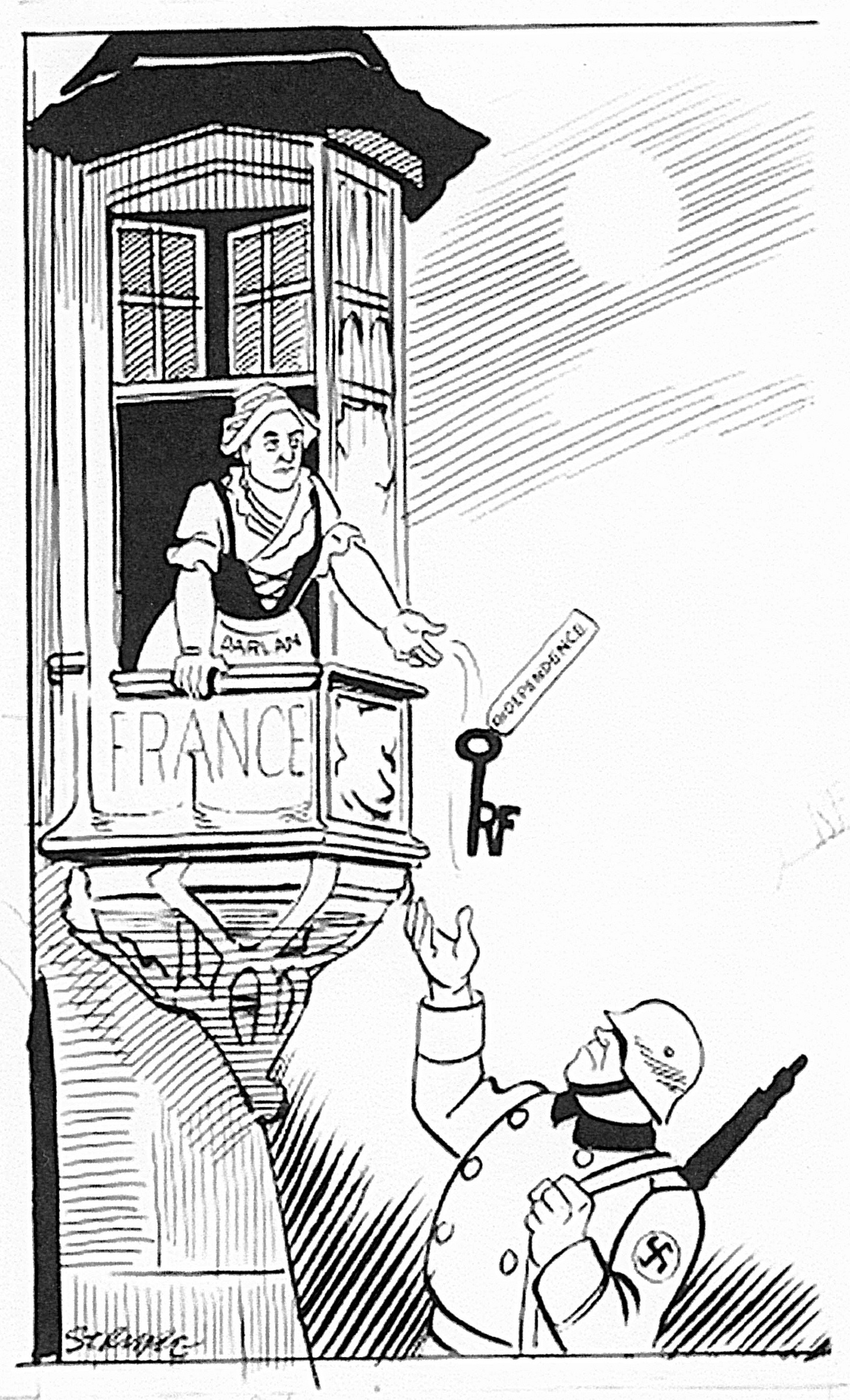

Many women across Europe embarked on such relationships with Germans during the war. They justified their actions by saying that relationships based on love were not a crime, that matters of the heart have nothing to do with politics, or that ‘love is blind’. But in the eyes of their communities, this was no excuse. Sex, if it was with a German, was political. It came to represent the subjugation of the continent as a whole: a female France, Denmark or Holland being ravished by a male Germany. Just as importantly, it also came to represent the emasculation of European men. These men, who had already shown themselves impotent against the military might of Germany, now found themselves communally cuckolded by their own womenfolk.

The number of sexual relationships that took place between European women and Germans during the war is quite staggering. In Norway as many as ten percent of women aged between 15 and 30 had German boyfriends during the war. If the statistics on the number of children born to German soldiers are anything to go by, this was by no means unusual: the numbers of women who slept with German men across western Europe can easily be numbered in the hundreds of thousands.

Resistance movements in occupied countries came up with all kinds of excuses for the behaviour of their women and girls. They characterised women who slept with Germans as ignorant, poor, and even mentally defective. They claimed that women were raped, or that they only slept with Germans out of economic necessity. While this was undoubtedly the case for some, recent surveys show that women who slept with German soldiers came from all classes and all walks of life. On the whole, European women slept with Germans not because they were forced to, or because their own men were absent, or because they needed money or food – but simply because they found the strong, ‘knightly’ image of the German soldiers intensely attractive, especially compared to the weakened image they had of their own menfolk. In Denmark, for example, wartime pollsters were shocked to discover that 51% of Danish women openly admitted to finding German men more attractive than their own compatriots.

Nowhere was this need more keenly felt than in France. In a nation where the huge, almost entirely male German presence, was matched by a corresponding absence of French men – two million of whom were prisoners or workers in Germany – it is unsurprising that the Occupation itself was often seen in sexual terms. France had become a ‘slut’, giving herself up to Germany with the Vichy government acting as her pimp. As Jean-Paul Sartre noted after the war, even the collaborationist press tended to represent the relationship between France and Germany as a union ‘in which France was always playing the part of the woman.’

Even those who still felt patriotic in the face of this were obliged to register a sense of sexual humiliation. Writing in 1942, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry suggested that all Frenchmen were tainted by an unavoidable feeling of being cuckolded by the war, but that they should not allow this shame to destroy their inate sense of patriotism:

Does a husband go from house to house crying out to his neighbours that his wife is a strumpet? Is it thus that he can preserve his honour? No, for his wife is one with his home. No, for he cannot establish his dignity against her. Let him go home to her, and there unburden himself of his anger. Thus, I shall not divorce myself from a defeat which surely will often humiliate me. I am part of France, and France is part of me.

Such emotions were experienced not only by Frenchmen, but also by men in all the occupied nations. As an airman fighting on behalf of the Free French, Saint-Exupéry was at least doing something to help liberate his country. For those who were stuck at home without any realistic means of fighting back, the frustration was more difficult to bear.

The liberation was an opportunity to put some of this right. By taking up arms once more, and participating in the invasion of their own country, French men had a chance to redeem themselves both in the eyes of their womenfolk and in the eyes of the world. This is perhaps one reason why Charles de Gaulle became such an important symbol for the French during the war. In contrast to the effeminate supplication of Vichy, de Gaulle had never surrendered his martial spirit, and stubbornly refused to bend to anyone else’s will, including that of his allies. The speeches he broadcast on the BBC were littered with masculine references to ‘Fighting France’, the ‘proud, brave and great French people’, the ‘military strength of France’ and the ‘aptitude for warfare of our race’. In a speech to the Consultative Assembly in Algiers in the run-up to the D-Day landings, de Gaulle praised

The work of our magnificent troops…the ardour of our units as they prepare for the great battle; the spirit of our ships’ companies; the prowess of our gallant air squadrons; the heroic boys who fight in the Maquis without uniforms, and nearly without arms, but animated by the purest military flame…

Such words are often used by generals who wish to appeal to the martial spirit of their troops. But they are significant here because they contrast so strongly with the defeatist, ‘effeminate’ way that Vichy portrayed French military hopes.

The rehabilitation of French masculinity began in earnest after the D-Day landings in June 1944, when de Gaulle and his ‘Free French’ troops finally returned to France. In the following months, they won a series of military scoops. The first was the liberation of Paris, which was conducted exclusively by French troops under General Philippe Leclerc (despite American attempts to hold Leclerc in check while they organised a more coordinated assault with US divisions). The second was the arrival of French troops in Provence on 15 August, who fought all the way through to Alsace and eventually crossed into Germany to capture Stuttgart. On the way, they liberated Lyon, France’s second city – again, without American help. Slowly but surely they were beginning to redeem themselves for the military embarassment of 1940.

However, perhaps the greatest boost to French pride was the formation of something that the British and Americans did not have – a separate army within France itself, which rose up and fought the Germans from the inside. The Forces Françaises de l’Intérieur (F.F.I.) – or les fifis as they were affectionately and disparagingly known – were an amalgamation of all the most important French resistance groups under the nominal leadership of General Pierre Koenig. During the summer of 1944 they took control of town after town, often fighting alongside regular British and American forces. They liberated almost all of southwest France without any outside help whatsoever, and likewise cleared the region east of Lyon for Allied troops driving north from Marseilles.

The exploits of the FFI gave a huge psychological boost to French morale, and particularly to the morale of young French men, who flocked to join up in great numbers: between June and October 1944, the ranks of the FFI swelled from 100,000 to 400,000. While seasoned résistants tended from habit to keep a fairly low profile, these new recruits were enormously keen to flaunt their new-found virility. Allied soldiers often reported seeing them appear with ‘bandoleers of ammunition strung all about them’ or with ‘grenades hanging from shoulder and belt’, as they kept ‘letting off round after round into the air.’ According to Julius Neave, who served as a major in the British Royal Armoured Corps, they were perhaps more of a nuisance than they were worth: ‘They roar round in civilian cars knocking each other down and fighting pitched battles with everyone, including themselves, ourselves and the Boche.’ Even some of the French villagers characterised them as ‘young men… parading with FFI amulets and posing as heroes.’ But if they appeared a little too keen to prove themselves this was only because, unlike British and American men, they had for years been denied the opportunity to take up arms against Germany. Now, for the first time, they were presented with a chance to fight properly, openly – like men.

Unfortunately, this newfound display of virility also had its darker side. The sudden influx of young men into the ranks of the resistance pushed out many much more experienced female résistantes. Jean Bohec, for example, who was a well respected female explosives expert in Saint-Marcel, suddenly found herself sidelined. ‘I was told politely to forget about it. A woman isn’t supposed to fight when so many men are available. Yet I surely knew how to use a submachine gun better than lots of the FFI volunteers who had just got hold of these arms.’ During the last winter of the Occupation women were phased out of active participation in the Resistance, and the FTP issued orders to phase out women altogether. This is in direct contrast to countries like Italy and Greece, where significant numbers of women continued to fight for partisans on the front line right to the end of the war.

If ‘good’ women were pushed aside by this sudden reassertion of French masculinity, then ‘bad’ women who had ‘cuckolded’ the nation were treated much more harshly. In the immediate aftermath of the liberation, the FFI turned upon these ‘horizontal collaborators’ en masse. In most cases the punishment they meted out was that of head shaving, which was often conducted in public in order to maximise the humiliation for the women involved. After the liberation, head-shaving ceremonies were carried out in every department of France.

A British artillery officer described a typical ceremony when he wrote about his experiences in northern France after the war:

At St André d’Echauffeur, where people showered us with flowers as we passed, others proffering bottles, a grim scene was being enacted in its market place – the punishment of a collaborator said to be une mauvaise femme. Seated in a chair while a barber shaved her head to the crown, she attracted a crowd of onlookers, among them, as I learned later, some Maquis and a Free French officer. The woman’s mother was also present and as the barber cropped her daughter, she stamped, raved and gesticulated frantically outside the circle of watchers. The woman was of some spirit. For, with her head fully cropped, she jumped to her feet and cried ‘Vive les Allemands,’ whereupon someone picked up a brick and felled her.